I learned a lot, as I always do at these round tables. And we shared our thoughts on the latest round of DC comics. Both Dan and Chris had read far more of them than I had, but we still managed to find some gems and some duds.

Wednesday, October 12, 2011

The BAMF Podcast

Mike Lafferty, good friend and drunkard, hosted a podcast last evening and we had a couple of wonderful co-hosts including Green Ronin freelancer, political science professor, and cynic Chris McGlothlin, and IDW veteran and comic creator and game designer Dan Taylor.

Wednesday, October 5, 2011

The Book is Out

I am very pleased to note that my first academic book, "Superheroes of the Round Table: Comics Connections to Medieval and Renaissance Literature", is now out. It is published by McFarland, and went to print last week. I got a stack of ten in the mail today.

I am very pleased to note that my first academic book, "Superheroes of the Round Table: Comics Connections to Medieval and Renaissance Literature", is now out. It is published by McFarland, and went to print last week. I got a stack of ten in the mail today.McFarland assures me an electronic version of the book will be available through Amazon, but there is no sign of it yet. In fact, Amazon still reports the book as coming out in January. But interested parties can buy directly from McFarland. When the digital copy comes out, I will spread the word.

Thursday, September 29, 2011

ENG 12S: Comics go to War

So just to prove you can't keep a good War down, my summer course which was cancelled at the last minute lives again as a last-minute addition to a Fall quarter with too many students and not enough courses.

The final reading list is a very painful compromise.

The final reading list is a very painful compromise.

Captain America Comics (1941)

Truth: Red, White & Black

Blazing Combat!

Blackhawk: Blood & Iron

Enemy Ace

It Was a War of the Trenches

The 'Nam

Safe Area Gorazde

Unknown Soldier: Haunted House

The great tragedy is Fax from Sarajevo, which is out of print and not in Dark Horse's digital comics library. With 60 students, I can't rely on a single personal copy put on reserve. UCR's Eaton Collection is very hit-or-miss with war comics, and it's usually miss. We have one issue of Two-Fisted Tales, for example. I wanted to at least look at Haunted Tank, but it and the other DC collections are all out of print; even Enemy Ace is going to be a real gamble, and it is the least popular of all those books.

But my students will be able to pick another war comic of their choice for their research paper, so there is some flexibility in there and I am sure that someone will do the other great war comics which we don't have access to in large quantities, or cannot get in time for a class which started one week into the quarter.

Tip of the Hat to Corey Creekmur, who recommended War of the Trenches and Blazing Combat. My old friend Dan Brophy reminded me of Chaykin's Blackhawk, and Nicole suggested Truth, which is especially useful as it can be read through Marvel's Digital Comics library, which means we can read it right away and we don't have to worry about ordering from Amazon.

Saturday, July 16, 2011

Vigilance Press Nominated for Ennie Award

For a couple of years now I have been publishing game material through the fine folks at Vigilance Press, who have this week been nominated for "Fan Favorite Publisher".

Vote Here

I first wrote to Charles Rice, the captain of this ship, when I was looking for a publisher to help with Arthur Lives! I chose Chuck because of all the books he had done over the years; he has a great love of the hobby, and he's prolific as hell. I knew I didn't want to deal with the business end of game publishing and I knew I could trust him. He took a chance and gave AL a home; we have put out three books for that game and I remain very proud of all of them. I would love to do more, as Arthur and modern magic are personal faves of mine. But, more importantly, Charles' reputation has been validated time and again since that first book. He's super supportive, knows what works, and is as honest as the day is long.

Vote Here!

I was tinkering on the next book in the AL saga when Chuck asked me if I had anything I wanted to write for ICONS. It took me 24 hours to realize that I could finally bring to print a book I had wanted to do for something like ten years, the Field Guide to Superheroes. We've done three of the four volumes and, once again, Chuck, together with Dan House and Mike Lafferty and Jessica, have allowed me to complete a long time project. It looks phenomenal and reception has been pretty positive. My biggest challenge is that the characters Dan has made up all look cooler than the ones I have made up; if that's my biggest problem I will take that any day.

Vote Here!

In between all of this, Mike has graciously invited me in to participate in various podcasts, in which we talk to authors and artists. I can talk about gaming and comics all day long, but in addition to plugging Vigilance books we've also gotten to talk to people like writers Ron Marz and Dan Abnett, or up and coming artist Ulises Farinas. It's wonderful to be part of a group that has such a positive reputation and which is embraced by fans. I am wise enough to know that my few books have nothing to do with this fact. Mike, Chuck, Steve Perrin and the rest far overshadow me through their creation of a complete World at War filled with super-Nazis and their lantern-jawed foes. But it is righteous company, and I am fortunate to be counted among them.

Stay Vigilant, everyone!

Vote Here

I first wrote to Charles Rice, the captain of this ship, when I was looking for a publisher to help with Arthur Lives! I chose Chuck because of all the books he had done over the years; he has a great love of the hobby, and he's prolific as hell. I knew I didn't want to deal with the business end of game publishing and I knew I could trust him. He took a chance and gave AL a home; we have put out three books for that game and I remain very proud of all of them. I would love to do more, as Arthur and modern magic are personal faves of mine. But, more importantly, Charles' reputation has been validated time and again since that first book. He's super supportive, knows what works, and is as honest as the day is long.

Vote Here!

I was tinkering on the next book in the AL saga when Chuck asked me if I had anything I wanted to write for ICONS. It took me 24 hours to realize that I could finally bring to print a book I had wanted to do for something like ten years, the Field Guide to Superheroes. We've done three of the four volumes and, once again, Chuck, together with Dan House and Mike Lafferty and Jessica, have allowed me to complete a long time project. It looks phenomenal and reception has been pretty positive. My biggest challenge is that the characters Dan has made up all look cooler than the ones I have made up; if that's my biggest problem I will take that any day.

Vote Here!

In between all of this, Mike has graciously invited me in to participate in various podcasts, in which we talk to authors and artists. I can talk about gaming and comics all day long, but in addition to plugging Vigilance books we've also gotten to talk to people like writers Ron Marz and Dan Abnett, or up and coming artist Ulises Farinas. It's wonderful to be part of a group that has such a positive reputation and which is embraced by fans. I am wise enough to know that my few books have nothing to do with this fact. Mike, Chuck, Steve Perrin and the rest far overshadow me through their creation of a complete World at War filled with super-Nazis and their lantern-jawed foes. But it is righteous company, and I am fortunate to be counted among them.

Stay Vigilant, everyone!

Saturday, July 2, 2011

Interview with Ron Marz

Last week I got together with Mike Lafferty of Vigilance Press to do an interview with Ron Marz. Ron is a distinguished writer and editor whose comics cred includes many, many books including the last 70+ issues of Witchblade, some of my favorite CrossGen titles (Mystic and Sojourn), a long run on Green Lantern (in which he helped create the character of Kyle Rayner), and on and on.

Ron very graciously allowed us to ask not only about his recent work at Top Cow, but also his experiences at CrossGen and the fact that he wrote the scene which Gail Simone's infamous "Women in Refrigerators" tagline is named after. I learned a lot about writing and the creative process, and found Ron's thoughts on DC's relaunch to be quite interesting. He's writing their new Voodoo book, by the way.

You can listen to the interview here.

Ron very graciously allowed us to ask not only about his recent work at Top Cow, but also his experiences at CrossGen and the fact that he wrote the scene which Gail Simone's infamous "Women in Refrigerators" tagline is named after. I learned a lot about writing and the creative process, and found Ron's thoughts on DC's relaunch to be quite interesting. He's writing their new Voodoo book, by the way.

You can listen to the interview here.

Wednesday, June 29, 2011

Field Guide to Super Heroes, Volume 3

It took a while for the third volume of this book to come out, but it is very exciting to see it on sale, and the fourth and final volume should take much less time. I hope to do a podcast with Dan, who provided all the art for this book as usual, sometime soon. You can find volume 3 of the Field Guide at RPGNow.

It took a while for the third volume of this book to come out, but it is very exciting to see it on sale, and the fourth and final volume should take much less time. I hope to do a podcast with Dan, who provided all the art for this book as usual, sometime soon. You can find volume 3 of the Field Guide at RPGNow.There's only one volume left; we have the last ten archetypes to cover and I am starting on that project tomorrow. With any luck, the entire Field Guide will be out by GenCon, and then I can start on the M&M 3rd edition version and the Field Guide to Super Villains.

Which should be very useful to everyone, since you can never have too many villains.

Friday, June 10, 2011

Frank Miller vs. William Blake

Today Comics Alliance posted this wonderful piece by Louie Joyce, a portrait of Frank Miller made up of quotes from his work. Perhaps because I was trained by Robert Essick, one of the world's leading Blake scholars, the moment I saw this portrait I immediately thought of Blake's Laocoon. This piece, perhaps his last artistic work before his death, depicts the famous statue surrounded by Blake's thoughts on art, God, science, and money. According to Essick, the story goes like this:

[Samuel] Palmer was showing [John Clarke] Strange an impression of the print [in 1859] and told Strange that, when Blake gave Palmer the print, Blake said "you will find my creed there." Thus the comment is second hand, but the authority is pretty good; I doubt that either Palmer or Strange made it up. This statement was first recorded in G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records, 2nd ed. (2004), p. 726.The connection between Blake and comics has been examined before. Blake's work is not comics, but it is an amazing body of text + image in combination that has influenced comics scholars like Donald Ault and comics creators like Alan Moore. Blake appears in Moore's From Hell, but really stars as the subject of Moore's five part poetry sequence Angel Passage in which he, and I shit you not, attempted to conjure up the spirit of William Blake during a live performance in the Tate Gallery.

As to who would win in this ultimate psycho political throw down, all I can say is that Blake had a temper, worked with his arms every day of his adult life, and almost got thrown in jail when he roughed up a soldier of the King. Miller is kind of a wimpy kid. So I'm just sayin.

If you can't read Blake's lines, you can find a good transcription here.

You can see more of William Blake's amazing text/image combinations at the Blake Archive.

Wednesday, June 8, 2011

Interview with Dan Abnett

Last month I had the very good fortune, along with Mike Lafferty, to interview Dan Abnett as part of the Vigilance Press podcast. In particular, I wanted to ask Dan about his portrayal of women in comics, since he had been assigned both the Wonder Woman and Lois Lane characters for Flashpoint. Also, Dan has some great insights on collaboration in comics, something I have always wanted to be better at.

But I made a classic interview error: I forgot to look up the subject's bibliography before the interview, or else I would have remembered that Dan also wrote Knights of Pendragon, which is one of the most interesting of the neo-Arthurian comics and the subject of several pages in my upcoming book, "Superheroes of the Round Table: Comics Connections to Medieval and Renaissance Literature". I can't believe I missed my chance to ask Dan about that book!

You can listen to the interview here.

But I made a classic interview error: I forgot to look up the subject's bibliography before the interview, or else I would have remembered that Dan also wrote Knights of Pendragon, which is one of the most interesting of the neo-Arthurian comics and the subject of several pages in my upcoming book, "Superheroes of the Round Table: Comics Connections to Medieval and Renaissance Literature". I can't believe I missed my chance to ask Dan about that book!

You can listen to the interview here.

Monday, June 6, 2011

ENG 140J Final Reading List

This is the final reading list for my just completed course on the Superhero Narrative. Like many such lists, it is the result of many compromises. But it serves as a useful point of departure.

Chapter One: The Superhero Origin

Action Comics #1 in Superman in the Forties

Superman #1 in Superman Archives

Film: Superman: The Movie

Umberto Eco, “The Myth of Superman” in Arguing Comics, p 146-164

Peter Coogan, “The Definition of the Superhero” in A Comics Studies Reader, p 77-93

Detective Comics #27 in Batman Archives, volume 1

Batman: Year One

Amazing Fantasy #15 in Marvel Masterworks: The Amazing Spider-Man, volume 1.

Ultimate Spider-Man 1-7

"The Secret Untold Relationship of Biblical Midrash and Comic Book Retcon", A. David Lewis

Chapter Two: Nemesis

Film: Unbreakable, M Knight Shyamalan

The Killing Joke, Alan Moore & Brian Bolland

Kathrin Bower, “Holocaust Avengers: From ‘The Master Race’ to Magneto”

X-Men 150, Chris Claremont & Dave Cockrum

Craig Fischer, “Fantastic Fascism: Jack Kirby, Nazi Aesthetics, and Theweleit’s Male Fantasies”

"The Social Modes of Heroization and Vilification in Bram Stoker's Dracula", Ana Gal

Triumph & Torment, Roger Stern & Mike Mignola

Novel: Soon I Will Be Invincible

Icon #1 and Hardware #1

Ch.1 of Caped Crusaders 101: "Black Heroes for Hire" by Jeffrey Kahan and Stanley Stewart

Select pages from Spawn vol. 1 (adding up two about 3 issues worth)

Ultimates #2

Alias (excerpts)

"Comic Book Masculinity and the New Black Superhero" by Jeffery A. Brown

"What's Going On? Black Masculinity in the Marvel Age", Michael van Dyke

Chapter Three: Love

Robert Lendrum, “Queering Super-Manhood: Superhero Masculinity, Camp and Public Relations as a Textual Framework”

Frank Bamlett, "The Confluence of Heroism, Sissyhood, and Camp in The Rawhide Kid: Slap Leather,” ImageText 5.1

Fantastic Four Annual 3

Amazing Spider-Man 121

Astro City 6, “Dinner at Eight”

Astro City 1/2, “The Nearness of You”

Ultra: 7 Days

Television: Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman, “Ultra Woman,” Season 3, episode 7

Chapter Four: Friendship

Novel: The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, Michael Chabon

Film: Thor

"The Legend of Master Legend", Joshuah Bearman, Rolling Stone

"Real Life Superheroes Fight City Crime ... In Costume", NPR interview with Phoenix Jones and DC Guardian

"Homemade Heroes Offer Local Law Enforcement", San Diego Tribune (Jan 17 2009)

Alan Moore on Glory

"No Capes! Uber Fashion and How Luck Favors the Prepared", Vicki Caraminas

Television: Buffy the Vampire Slayer (Season 6 episode 7), “Once More with Feeling”

Online: Dr. Horrible’s Sing Along Blog

Television: 60 Minutes, “The Musical Spectacle of Spider-Man”

Chapter Five: Death

The Death of Captain Marvel

Jose Alaniz, “Death and the Superhero: The Silver Age and Beyond”

Wilbur Farley, “’The Disease Resumes Its March to Darkness’: The Death of Captain Marvel and the Metastasis of Empire"

“The Dark Phoenix Saga”: X-Men 101-108 and Uncanny X-Men 129-138

Film: Spider-Man 2

Arnold T. Blumberg, “The Night Gwen Stacy Died: The End of Innocence and the ‘Last Gasp of the Silver Age’”

Abraham Kawa, “The Universe She Died In: The Death of Lives of Gwen Stacy”

“Kraven’s Last Hunt": Web of Spider Man 31-32, Amazing Spider-Man 293-294, Spectacular Spider-Man 131-132

Vigilante #50

Chapter One: The Superhero Origin

Action Comics #1 in Superman in the Forties

Superman #1 in Superman Archives

Film: Superman: The Movie

Umberto Eco, “The Myth of Superman” in Arguing Comics, p 146-164

Peter Coogan, “The Definition of the Superhero” in A Comics Studies Reader, p 77-93

Detective Comics #27 in Batman Archives, volume 1

Batman: Year One

Amazing Fantasy #15 in Marvel Masterworks: The Amazing Spider-Man, volume 1.

Ultimate Spider-Man 1-7

"The Secret Untold Relationship of Biblical Midrash and Comic Book Retcon", A. David Lewis

Chapter Two: Nemesis

Film: Unbreakable, M Knight Shyamalan

The Killing Joke, Alan Moore & Brian Bolland

Kathrin Bower, “Holocaust Avengers: From ‘The Master Race’ to Magneto”

X-Men 150, Chris Claremont & Dave Cockrum

Craig Fischer, “Fantastic Fascism: Jack Kirby, Nazi Aesthetics, and Theweleit’s Male Fantasies”

"The Social Modes of Heroization and Vilification in Bram Stoker's Dracula", Ana Gal

Triumph & Torment, Roger Stern & Mike Mignola

Novel: Soon I Will Be Invincible

Icon #1 and Hardware #1

Ch.1 of Caped Crusaders 101: "Black Heroes for Hire" by Jeffrey Kahan and Stanley Stewart

Select pages from Spawn vol. 1 (adding up two about 3 issues worth)

Ultimates #2

Alias (excerpts)

"Comic Book Masculinity and the New Black Superhero" by Jeffery A. Brown

"What's Going On? Black Masculinity in the Marvel Age", Michael van Dyke

Chapter Three: Love

Robert Lendrum, “Queering Super-Manhood: Superhero Masculinity, Camp and Public Relations as a Textual Framework”

Frank Bamlett, "The Confluence of Heroism, Sissyhood, and Camp in The Rawhide Kid: Slap Leather,” ImageText 5.1

Fantastic Four Annual 3

Amazing Spider-Man 121

Astro City 6, “Dinner at Eight”

Astro City 1/2, “The Nearness of You”

Ultra: 7 Days

Television: Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman, “Ultra Woman,” Season 3, episode 7

Chapter Four: Friendship

Novel: The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, Michael Chabon

Film: Thor

"The Legend of Master Legend", Joshuah Bearman, Rolling Stone

"Real Life Superheroes Fight City Crime ... In Costume", NPR interview with Phoenix Jones and DC Guardian

"Homemade Heroes Offer Local Law Enforcement", San Diego Tribune (Jan 17 2009)

Alan Moore on Glory

"No Capes! Uber Fashion and How Luck Favors the Prepared", Vicki Caraminas

Television: Buffy the Vampire Slayer (Season 6 episode 7), “Once More with Feeling”

Online: Dr. Horrible’s Sing Along Blog

Television: 60 Minutes, “The Musical Spectacle of Spider-Man”

Chapter Five: Death

The Death of Captain Marvel

Jose Alaniz, “Death and the Superhero: The Silver Age and Beyond”

Wilbur Farley, “’The Disease Resumes Its March to Darkness’: The Death of Captain Marvel and the Metastasis of Empire"

“The Dark Phoenix Saga”: X-Men 101-108 and Uncanny X-Men 129-138

Film: Spider-Man 2

Arnold T. Blumberg, “The Night Gwen Stacy Died: The End of Innocence and the ‘Last Gasp of the Silver Age’”

Abraham Kawa, “The Universe She Died In: The Death of Lives of Gwen Stacy”

“Kraven’s Last Hunt": Web of Spider Man 31-32, Amazing Spider-Man 293-294, Spectacular Spider-Man 131-132

Vigilante #50

Monday, May 30, 2011

"Superheroes of the Round Table: Comics Connections to Medieval and Renaissance Literature"

A tip of the hat to Michael Torregrossa and his Medieval Comics Project who noticed that my upcoming book is now available for pre-order from McFarland & Co.

This will be my first academic book, and the project began as my dissertation, An Imaginary Mongoose: Comics, Canon, and the Superhero Romance. Normally dissertations require extensive rewriting because they are written for the idiosyncratic requirements of a three person committee, but my case was a bit different. I had always written it for publication, and the only major shortcoming of the book was that it was a a bit short. Also, I did not really like the chapter flow, which demonstrated a bit too clearly that I was running out of time as work on the diss came to a close.

So first I revised everything to change it from a book written for Renaissance scholars who know little about comics, to a book written for comics scholars who know little about Renaissance literature. Then I added a new chapter on Shakespeare and comics, which let me write about Alan Moore, Claremont, and Peter David in addition to the obligatory Gaiman, and which ended up being the biggest piece of the final book. And then I reorganized by moving the chapter on Kirby, Ben Jonson and Eisner from 4th place to 2nd, following the Spenser/Iron Man chapter. The Jonson led well into the Shakespeare material for chapter 3, leaving my arbitrary survey of Arthurian themes in comics for chapter 4, serving as a good introduction for the final chapter on Grant Morrison, Invisibles, JLA, and Seven Soldiers of Victory.

I always knew McFarland would change the name of the book. It doesn't bother me. I happen to love the original title, but in my mind that book has already been published. "An Imaginary Mongoose" is my original dissertation. This is a different book, significantly larger, revised from front to back, better informed and aimed at a different audience.

I'm also extremely gratified that, despite all my anxieties and concerns, only a single image from my initial list of 67 has been cut. We're using these illustrations under academic fair use and I didn't have to struggle for any permissions. What a relief! Some of my fellow comics scholars have been delayed a year or more trying to get permissions, permissions which should not even be necessary.

We're hoping for a release in the Fall of this year, but Winter (perhaps sliding into early next year) is a possibility. The book is still in copy editing, but with any luck, by Christmas, it will be out.

This will be my first academic book, and the project began as my dissertation, An Imaginary Mongoose: Comics, Canon, and the Superhero Romance. Normally dissertations require extensive rewriting because they are written for the idiosyncratic requirements of a three person committee, but my case was a bit different. I had always written it for publication, and the only major shortcoming of the book was that it was a a bit short. Also, I did not really like the chapter flow, which demonstrated a bit too clearly that I was running out of time as work on the diss came to a close.

So first I revised everything to change it from a book written for Renaissance scholars who know little about comics, to a book written for comics scholars who know little about Renaissance literature. Then I added a new chapter on Shakespeare and comics, which let me write about Alan Moore, Claremont, and Peter David in addition to the obligatory Gaiman, and which ended up being the biggest piece of the final book. And then I reorganized by moving the chapter on Kirby, Ben Jonson and Eisner from 4th place to 2nd, following the Spenser/Iron Man chapter. The Jonson led well into the Shakespeare material for chapter 3, leaving my arbitrary survey of Arthurian themes in comics for chapter 4, serving as a good introduction for the final chapter on Grant Morrison, Invisibles, JLA, and Seven Soldiers of Victory.

I always knew McFarland would change the name of the book. It doesn't bother me. I happen to love the original title, but in my mind that book has already been published. "An Imaginary Mongoose" is my original dissertation. This is a different book, significantly larger, revised from front to back, better informed and aimed at a different audience.

I'm also extremely gratified that, despite all my anxieties and concerns, only a single image from my initial list of 67 has been cut. We're using these illustrations under academic fair use and I didn't have to struggle for any permissions. What a relief! Some of my fellow comics scholars have been delayed a year or more trying to get permissions, permissions which should not even be necessary.

We're hoping for a release in the Fall of this year, but Winter (perhaps sliding into early next year) is a possibility. The book is still in copy editing, but with any luck, by Christmas, it will be out.

Friday, May 13, 2011

Comics go to War

This is the course I will be teaching this summer at UCR. It's a lower division English course, so will not be aimed at English majors, but it does fulfill a breadth requirement for non-majors and English folks may still find it useful as pure credits.

Friday, May 6, 2011

Latest Podcast

This week I got to sit in on a Vigilance Press podcast with Chris McGlothlin, author of pretty much my entire shelf of Mutants & Masterminds books. Chris is a very thoughtful and generous guest, and we had a great time talking superhero comics, games, and films.

You can check it out here.

You can check it out here.

Tuesday, May 3, 2011

Moriarty: The Dark Chamber

My review of Daniel Corey's Moriarty: The Dark Chamber, published next week by Image, is up at Comic Book Therapy.

You can check it out here.

You can check it out here.

Tuesday, April 26, 2011

The Secret Life of Comic Scholars

So, there are people who study comic books for a living. I’m not just talking about Chris “Batmanologist” Sims and other bloggers, though we all read and enjoy such work. Rather, I am talking about professors at colleges and universities around the world who write books, teach classes, and do research on comics, including superhero comics.

There are a few times in the year when these people get together for a sort of high-brow version of SanDiego ComiCon. The International Comic Arts Forum is one — this year ICAF is going to be held at James Sturm’s Center for Cartoon Studies, which grants an MA in the making of comics. The Comic Arts Conference has been held at San Diego ComiCon for almost twenty years now, and has even branched out into a Bay Area cousin for WonderCon. But I’m not going to talk about any of those, because what happened this last week was the annual meeting of the International Popular Culture Association, held in San Antonio, Texas. This is a massive gathering of some three thousand scholars to talk about everything from Twilight and Harry Potter to myth and folklore, the Grateful Dead, or House. The PCA is divided into many smaller “Areas”, and one of the largest — I think we’re beat out by the Science Fiction area and one or two others — is Comic Art and Comics. This year, there were over a hundred graduate students, professors, and “Independent Scholars” (which is a short way of saying ‘really smart people who haven’t been hired by a University’) who came to San Antonio to present some of their research on comics.

When you’re coming to PCA, you arrive Tuesday night or Wednesday morning and the shindig lasts through Saturday. It travels around through various cities, some popular (New Orleans, Boston), some not (St. Louis). It’s almost always over Easter, because that is when travel and hotel prices are lowest, and professors and grad students are cheap. Most people try to get money from their universities, which after all insist we do stuff like this, but money is hard to come by and this year a lot of people who usually come for the whole conference instead had to budget for only a day or two. More than a few people say they are coming, and then either cancel at the last minute because they didn’t get funding from their school or simply don’t show up at all. This year, about 1 out of every 7 people didn’t show up, which was unusually high.

The PCA conference takes almost everyone who wants to come. I guess if you submitted a paper called, “Watchmen ROX and I wanna talk about it!” we might not take you, but just about anyone who wants to brave the trip is welcome. This makes it a great way for new scholars, young students, and others who might be nervous about presenting their work to get some experience. It’s also a great way for old friends to keep in touch. I have many friends at PCA that I see only once a year, for three or four days, while we all get egghead. Each individual person presents for 15-20 minutes; three or four of these papers are grouped together into a panel. We had about 20 panels this year, which is close to the record. Panels start around 8am and go all day long. They used to give us scheduled breaks for lunch and dinner, but in the desire to squeeze as many people as possible into four days, those breaks have gotten tossed and now, if you want to fulfill basic bodily needs like eating you have to miss someone’s panel to do it. Which stinks.

So what are these panels and papers about, right? Many are on the topics you would imagine — if you put five comic geeks in a room you can pretty much predict they’re eventually going to talk about Alan Moore and Grant Morrison, or Civil War and Blackest Night. But there’s also a strong contingent which wants nothing to do with superhero comics and will instead speak about the undergrounds, or Jeff Smith’s Bone, or MAD magazine, or EC comics, the Comics Code, Peanuts, Joe Sacco’s Palestine, or anything else which is art with boxes drawn around it. There’s a pretty strong international contingent that does work on French, Italian, or other European comics like Herge, and a pretty healthy Manga contingent which actually has its own area.

What PCA really shows off is the rich diversity of comics studies. There really is something for everyone here. Since I am teaching a class on superheroes this quarter, my mind was on “long underwear stories,” so I took away copies of papers that argued:

We’re not all business at these conferences. We spend a lot of time hanging out at the hotel bar, going out to eat, or occasionally looking for sweet deals. At Toronto a few years back I found a great comic store and got to stock up on some trades I had missed. About four years ago we started to poke a little fun at ourselves and we created the Institute for Korvac Studies, a “mock panel” where we make up papers about the man-god that is Korvac and we read these ridiculous papers while trying to keep a straight face. We even hand out an award, the Korvie, which began as a Ken doll, but we cut him off at the waist, taped him to a box, and spray painted the whole thing gold. You should see the looks people get when they take that on the plane.

A lot of the papers presented at PCA and similar conferences eventually get published. John Lent, who edits and publishes the International Journal of Comic Art, headhunts for articles there every year. Others go to Mechademia, a book collection on anime and manga put out by the Minneapolis College of Art and Design. More still end up in Image/Text, a wonderful online journal for comics research published by the University of Florida. You should check some of these out. Editors and publishers also go to PCA and use the time to meet with potential authors or to renew old acquaintances. My first book contract came out of a PCA meeting, and this year I talked with some editors about my next project. There’s a lot of networking to do, and you also find out what everyone else is working on. Working in a vacuum is sort of the exact opposite of what we do; as critics and scholars, our job is to know what everyone else is doing and build on that. This means ourbusiness is a lot more about social skills than outsiders might realize.

By Saturday night, most of us are pretty wasted. We’re missing our pets, our kids, and our own beds. Sunday sees us roll out of the hotels and to the airports for the long trip home. And then there’s the flurry of emails, the “Hey, can I get a copy of your paper?” queries, and the “See you next year!” notes, the Facebook status updates and the frenzied effort to catch up on all that grading we put off for a week. A lot of people work very hard to make these conferences successful, and without them, where would we all be?

Well, I guess we’d be blogging about it, instead of talking in front of a room full of eggheads. But it just wouldn’t be the same.

There are a few times in the year when these people get together for a sort of high-brow version of SanDiego ComiCon. The International Comic Arts Forum is one — this year ICAF is going to be held at James Sturm’s Center for Cartoon Studies, which grants an MA in the making of comics. The Comic Arts Conference has been held at San Diego ComiCon for almost twenty years now, and has even branched out into a Bay Area cousin for WonderCon. But I’m not going to talk about any of those, because what happened this last week was the annual meeting of the International Popular Culture Association, held in San Antonio, Texas. This is a massive gathering of some three thousand scholars to talk about everything from Twilight and Harry Potter to myth and folklore, the Grateful Dead, or House. The PCA is divided into many smaller “Areas”, and one of the largest — I think we’re beat out by the Science Fiction area and one or two others — is Comic Art and Comics. This year, there were over a hundred graduate students, professors, and “Independent Scholars” (which is a short way of saying ‘really smart people who haven’t been hired by a University’) who came to San Antonio to present some of their research on comics.

When you’re coming to PCA, you arrive Tuesday night or Wednesday morning and the shindig lasts through Saturday. It travels around through various cities, some popular (New Orleans, Boston), some not (St. Louis). It’s almost always over Easter, because that is when travel and hotel prices are lowest, and professors and grad students are cheap. Most people try to get money from their universities, which after all insist we do stuff like this, but money is hard to come by and this year a lot of people who usually come for the whole conference instead had to budget for only a day or two. More than a few people say they are coming, and then either cancel at the last minute because they didn’t get funding from their school or simply don’t show up at all. This year, about 1 out of every 7 people didn’t show up, which was unusually high.

The PCA conference takes almost everyone who wants to come. I guess if you submitted a paper called, “Watchmen ROX and I wanna talk about it!” we might not take you, but just about anyone who wants to brave the trip is welcome. This makes it a great way for new scholars, young students, and others who might be nervous about presenting their work to get some experience. It’s also a great way for old friends to keep in touch. I have many friends at PCA that I see only once a year, for three or four days, while we all get egghead. Each individual person presents for 15-20 minutes; three or four of these papers are grouped together into a panel. We had about 20 panels this year, which is close to the record. Panels start around 8am and go all day long. They used to give us scheduled breaks for lunch and dinner, but in the desire to squeeze as many people as possible into four days, those breaks have gotten tossed and now, if you want to fulfill basic bodily needs like eating you have to miss someone’s panel to do it. Which stinks.

So what are these panels and papers about, right? Many are on the topics you would imagine — if you put five comic geeks in a room you can pretty much predict they’re eventually going to talk about Alan Moore and Grant Morrison, or Civil War and Blackest Night. But there’s also a strong contingent which wants nothing to do with superhero comics and will instead speak about the undergrounds, or Jeff Smith’s Bone, or MAD magazine, or EC comics, the Comics Code, Peanuts, Joe Sacco’s Palestine, or anything else which is art with boxes drawn around it. There’s a pretty strong international contingent that does work on French, Italian, or other European comics like Herge, and a pretty healthy Manga contingent which actually has its own area.

What PCA really shows off is the rich diversity of comics studies. There really is something for everyone here. Since I am teaching a class on superheroes this quarter, my mind was on “long underwear stories,” so I took away copies of papers that argued:

- In Blackhawk, Howard Chaykin uses fascism to tell liberal, left-wing stories.

- The Tony Stark of the films uses technology to become human, while in the comics the same technology makes him less human.

- Wonder Woman is stuck in a “husband quest”, the female version of the traditional heroic quest, and she can’t fulfill it even if we would want her to.

- Warren Ellis uses Planetary to not only critique other comics, but to set his own story up as a comic that cannot be critiqued.

- Morrison made the Joker into a magic spell which Heath Ledger successfully performed.

- The essential quality of the 20th century hero is speed, and the faster he is, the more heroic he is perceived.

- Stan Lee wrote J Jonah Jameson to be a representation of Fredric Wertham, author of Seduction of the Innocent.

We’re not all business at these conferences. We spend a lot of time hanging out at the hotel bar, going out to eat, or occasionally looking for sweet deals. At Toronto a few years back I found a great comic store and got to stock up on some trades I had missed. About four years ago we started to poke a little fun at ourselves and we created the Institute for Korvac Studies, a “mock panel” where we make up papers about the man-god that is Korvac and we read these ridiculous papers while trying to keep a straight face. We even hand out an award, the Korvie, which began as a Ken doll, but we cut him off at the waist, taped him to a box, and spray painted the whole thing gold. You should see the looks people get when they take that on the plane.

A lot of the papers presented at PCA and similar conferences eventually get published. John Lent, who edits and publishes the International Journal of Comic Art, headhunts for articles there every year. Others go to Mechademia, a book collection on anime and manga put out by the Minneapolis College of Art and Design. More still end up in Image/Text, a wonderful online journal for comics research published by the University of Florida. You should check some of these out. Editors and publishers also go to PCA and use the time to meet with potential authors or to renew old acquaintances. My first book contract came out of a PCA meeting, and this year I talked with some editors about my next project. There’s a lot of networking to do, and you also find out what everyone else is working on. Working in a vacuum is sort of the exact opposite of what we do; as critics and scholars, our job is to know what everyone else is doing and build on that. This means ourbusiness is a lot more about social skills than outsiders might realize.

By Saturday night, most of us are pretty wasted. We’re missing our pets, our kids, and our own beds. Sunday sees us roll out of the hotels and to the airports for the long trip home. And then there’s the flurry of emails, the “Hey, can I get a copy of your paper?” queries, and the “See you next year!” notes, the Facebook status updates and the frenzied effort to catch up on all that grading we put off for a week. A lot of people work very hard to make these conferences successful, and without them, where would we all be?

Well, I guess we’d be blogging about it, instead of talking in front of a room full of eggheads. But it just wouldn’t be the same.

Friday, April 8, 2011

Vigilance Press Podcast

Every once in a while I do some podcasting with the fine folks at Vigilance Press, the roleplaying game publishers who have released my Field Guide to Superheroes and Arthur Lives! projects. This week we Skyped with Steve Perrin, a legend in the rpg community and a really nice guy to boot. Steve's latest release is a sourcebook for super heroics in the Golden Age. I've read more than a few of those over the years, but I thought this one stood out for it's up-front approach to the social issues of World War II and our desire to retcon it into something more progressive. It would have been easy to dodge these issues, but Steve knew better and instead highlighted the difference between the War the way it was, and the way we would like it to be remembered.

You can check the podcast out here:Clicky!

Originally we had intended to spend some time talking about the Comics Code, but i think we spent so much time talking about it here that we felt the conversation had already been done.

You can check the podcast out here:Clicky!

Originally we had intended to spend some time talking about the Comics Code, but i think we spent so much time talking about it here that we felt the conversation had already been done.

Friday, April 1, 2011

Video Blogging

With my new iPad fresh out of the box, I am experimenting with video blogging. In this first episode, I begin with the basic thesis of my Superhero Narrative course, and then use this to examine some aspects of Superman's origin, Kirby's New Gods, and the tension between fantasy and reality that we see in so many superhero comics.

YouTube apparently picks the dorkiest moment from the video. I swear i don't make funny faces for the entire thing, which is about 14 minutes.

YouTube apparently picks the dorkiest moment from the video. I swear i don't make funny faces for the entire thing, which is about 14 minutes.

Wednesday, March 30, 2011

The Comics Code

Next week I'll be doing a podcast with the folks from Vigilance Press, and our head honcho Charles Rice has asked that we take the opportunity to commemorate one more nail in the coffin of the Comics Code Authority -- an instrument of industry regulation which ensured that, for thirty years, superhero comics would remain children's literature.

That description of the Code might strike many comics fans as odd. For most, the Code is an excuse for a lot of righteous anger, usually aimed at Fredric Wertham and his book Seduction of the Innocent. The Code did a lot of damage to the superhero genre, and I am not here to say otherwise. But it's also important that we see the Code in context, and come to appreciate its long-term influence and ramifications, some of which are unexpected and which have resulted in some pretty great comics.

(I'll also note that I am teaching a class this semester on the Superhero narrative, and my students might find this brief summary helpful, especially as a launching point for further individual research.)

Anyone interested in learning the facts about the Code, and clearing their head of many misconceptions, are urged to read two books. The first, and in my opinion the more essential, is Amy Nyberg's Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics Code. (1) Amy tells the entire story of the Code, up to the mid '80s or so, when her book was published. This includes an examination of Wertham's methodology, the Kefauver Senate hearings in which William Gaines and others were brought forth to testify on the impact of comics on children, the eventual creation of the Code itself, its implementation through newstands and newspaper distribution channels, and the changes to the Code which took place in the 1970s and 1980s. Amy is a Professor of Communications at Seaton Hall University, a journalist to her very bones, and her unbiased approach allows her to write about people like Wertham without demonizing him, as so many comics readers are prone to do. One of the most valuable elements of her book is that it includes the actual language of the actual Code itself, in its various forms, allowing you and I and everyone else to read the damned thing and judge it for ourselves.

And what we see, when we read the Code and Amy's elegant unpacking of it, is that the Comics Code has to be read in the context of the effort to control the literature of children. That is, Wertham and Kefauver and the other people who had problems with comics of the 1950s approached the problem with this point of view: "Comics are read by children. And so we have a moral responsibility to police comic books, to protect our children from ideas too dangerous for them." There's a flaw in this argument, but it's not the issue of censorship. I think most people would agree that there are some books children should not be reading. The flaw is the assumption that comics are children's literature. But this flaw was accepted, wholesale, by the comic book publishers themselves, who then tried to defend comics as children's literature! What I am trying to get at here is pretty simple: While it is easy for us to get outraged and blame Fredric Wertham and others for "ruining comics", we should dole out equal blame to the publishers of the comics themselves, who agreed that comics were for kids, and would always be for kids.

Much like the motion picture industry, which created a system of self-policing so that they could avoid government interference, the comics industry agreed to self-censorship. But whereas the motion picture industry understood that not all movies were for children, the comics industry did not. Leaders in the comics industry effectively decided that all comics would be rated G. This is not the fault of Fredric Wertham, nor of Senator Kefauver. The Comics Code was a straightjacket sewed and fitted by the patient, for himself.

And it really is awful. The Code insists that all authority figures be portrayed in a sympathetic light, that no police officer, priest, or government figure ever be portrayed badly, or even be disobeyed. The Code insists that all criminals be portrayed as unhappy losers who get what's coming to them. Many people rail about the loss of EC Comics, a publisher of crime and horror comics whose entire line was more or less prohibited by the Code. But the real tragedy of the Comics Code was not just that it forced comics to be children's literature, but that it forced comics to be boring.

The first real blow to the Code came in the 1970s, when the Nixon administration approached Marvel Comics and asked Stan Lee to do a comic highlighting the dangers of drug use and abuse. The depiction of drug paraphernalia of any kind was explicitly forbidden by the Code. So, if Lee was to make the comic, that comic would be in violation of the Code. Marvel printed the comic, which became Amazing Spider-Man #86. (Look at the cover to the left, and you will notice that there is no seal in the top corner.) The publication of this comic led to a rewrite of the Code, lessening its restrictions, and opening the way for "Relevancy" comics like the famous "Hard Traveling Heroes" sequence in which Green Arrow learns that Speedy is "a junkie." But the Code was still in, and had, effect during this time period. If you look inside those Green Lantern/Green Arrow comics you can still see, for example, a panel in which a ring of children are holding knives on our heroes. But the knives, while clearly visible on the cover, are concealed with pools of black ink on the interiors. Because depicting a ring of murderous children with knives was still too much for DC, and for other publishers, at the time.

The second serious blow to the Code came with the creation of the comics specialty store. The Code was enforced through the system of newspaper distribution, the system which put comics on the shelves of 7-11 or your local drug store. (I read all my earliest comics sitting in the aisle at Sav-On Drugs in Anaheim, California.) But the comics shops which grew up around the country in the 1980s did not get their comics through this network. Which meant that a comic which violated the Code, and thus did not have the Code seal on the cover, could still be acquired by the comic shop, would still sell off the shelves, and would still make money for Marvel and DC. Because more and more comics were sold through these shops, and not on newstands or from drug stores, publishers began to print comics which circumvented the Code. And, thus, Watchmen and Dark Knight Returns, among other books.

By the 90s, Marvel and DC were both publishing large sections of their monthly run without Code approval. Those books which still had the Code seal were still intended to be readable by children, even though the demographics for comics were aging rapidly. Artists and writers continued to chafe. The Code was again revised and loosened, turned into a set of "internal documents", but there were still things you could not do. One of these things was the infamous "needle to the eye" motif, and when Todd McFarland drew such a panel, and refused to change it for his editors and publishers, this proved to be the straw that broke the camel's back, and we got Image Comics. Marvel left the Code a few years later, but DC continued to use it for some of its books because DC has always had a keener appreciation of the value of children readers. It's not a coincidence that the company which was creating Batman: The Animated Series was also still participating in the Code. DC also published Vertigo, and plenty of other books which did not use the Code, but they also wanted to have a large selection of books which, for example, Grandma could safely buy as a birthday present for her little boy. I honestly think Marvel left the code just because Joe Quesada was tired of dealing with the hassle of getting approval for every book. The content of the books didn't much change.

All of which leads us to the present, and DC's final decision to move away from the Code altogether and instead embrace a rating system similar to the one they already use on video games. I cannot help but think, with the benefit of hindsight, that this is what DC and other comics publishers should have pushed for from the beginning. But they could not, because they had already bought into the essential premise of their critics: that comics were for kids. That was an unfair assumption. But it was foolish to accept it. And the comics form paid the price. It has not yet recovered.

(1) -- The second book worth reading on this topic is Hajdu's The Ten Cent Plague: The Great Comic Book Scare and How It Changed America. Hajdu writes not as a journalist but as a storyteller and historian, which means his book has more of a narrative and is, in many ways, simply more fun to read. But it focused almost exclusively on the formation of the Code, and does not treat the Code's transformation in later decades. This makes it less useful to the comics scholar, but still a great book.

That description of the Code might strike many comics fans as odd. For most, the Code is an excuse for a lot of righteous anger, usually aimed at Fredric Wertham and his book Seduction of the Innocent. The Code did a lot of damage to the superhero genre, and I am not here to say otherwise. But it's also important that we see the Code in context, and come to appreciate its long-term influence and ramifications, some of which are unexpected and which have resulted in some pretty great comics.

(I'll also note that I am teaching a class this semester on the Superhero narrative, and my students might find this brief summary helpful, especially as a launching point for further individual research.)

Anyone interested in learning the facts about the Code, and clearing their head of many misconceptions, are urged to read two books. The first, and in my opinion the more essential, is Amy Nyberg's Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics Code. (1) Amy tells the entire story of the Code, up to the mid '80s or so, when her book was published. This includes an examination of Wertham's methodology, the Kefauver Senate hearings in which William Gaines and others were brought forth to testify on the impact of comics on children, the eventual creation of the Code itself, its implementation through newstands and newspaper distribution channels, and the changes to the Code which took place in the 1970s and 1980s. Amy is a Professor of Communications at Seaton Hall University, a journalist to her very bones, and her unbiased approach allows her to write about people like Wertham without demonizing him, as so many comics readers are prone to do. One of the most valuable elements of her book is that it includes the actual language of the actual Code itself, in its various forms, allowing you and I and everyone else to read the damned thing and judge it for ourselves.

And what we see, when we read the Code and Amy's elegant unpacking of it, is that the Comics Code has to be read in the context of the effort to control the literature of children. That is, Wertham and Kefauver and the other people who had problems with comics of the 1950s approached the problem with this point of view: "Comics are read by children. And so we have a moral responsibility to police comic books, to protect our children from ideas too dangerous for them." There's a flaw in this argument, but it's not the issue of censorship. I think most people would agree that there are some books children should not be reading. The flaw is the assumption that comics are children's literature. But this flaw was accepted, wholesale, by the comic book publishers themselves, who then tried to defend comics as children's literature! What I am trying to get at here is pretty simple: While it is easy for us to get outraged and blame Fredric Wertham and others for "ruining comics", we should dole out equal blame to the publishers of the comics themselves, who agreed that comics were for kids, and would always be for kids.

Much like the motion picture industry, which created a system of self-policing so that they could avoid government interference, the comics industry agreed to self-censorship. But whereas the motion picture industry understood that not all movies were for children, the comics industry did not. Leaders in the comics industry effectively decided that all comics would be rated G. This is not the fault of Fredric Wertham, nor of Senator Kefauver. The Comics Code was a straightjacket sewed and fitted by the patient, for himself.

And it really is awful. The Code insists that all authority figures be portrayed in a sympathetic light, that no police officer, priest, or government figure ever be portrayed badly, or even be disobeyed. The Code insists that all criminals be portrayed as unhappy losers who get what's coming to them. Many people rail about the loss of EC Comics, a publisher of crime and horror comics whose entire line was more or less prohibited by the Code. But the real tragedy of the Comics Code was not just that it forced comics to be children's literature, but that it forced comics to be boring.

The first real blow to the Code came in the 1970s, when the Nixon administration approached Marvel Comics and asked Stan Lee to do a comic highlighting the dangers of drug use and abuse. The depiction of drug paraphernalia of any kind was explicitly forbidden by the Code. So, if Lee was to make the comic, that comic would be in violation of the Code. Marvel printed the comic, which became Amazing Spider-Man #86. (Look at the cover to the left, and you will notice that there is no seal in the top corner.) The publication of this comic led to a rewrite of the Code, lessening its restrictions, and opening the way for "Relevancy" comics like the famous "Hard Traveling Heroes" sequence in which Green Arrow learns that Speedy is "a junkie." But the Code was still in, and had, effect during this time period. If you look inside those Green Lantern/Green Arrow comics you can still see, for example, a panel in which a ring of children are holding knives on our heroes. But the knives, while clearly visible on the cover, are concealed with pools of black ink on the interiors. Because depicting a ring of murderous children with knives was still too much for DC, and for other publishers, at the time.

The second serious blow to the Code came with the creation of the comics specialty store. The Code was enforced through the system of newspaper distribution, the system which put comics on the shelves of 7-11 or your local drug store. (I read all my earliest comics sitting in the aisle at Sav-On Drugs in Anaheim, California.) But the comics shops which grew up around the country in the 1980s did not get their comics through this network. Which meant that a comic which violated the Code, and thus did not have the Code seal on the cover, could still be acquired by the comic shop, would still sell off the shelves, and would still make money for Marvel and DC. Because more and more comics were sold through these shops, and not on newstands or from drug stores, publishers began to print comics which circumvented the Code. And, thus, Watchmen and Dark Knight Returns, among other books.

By the 90s, Marvel and DC were both publishing large sections of their monthly run without Code approval. Those books which still had the Code seal were still intended to be readable by children, even though the demographics for comics were aging rapidly. Artists and writers continued to chafe. The Code was again revised and loosened, turned into a set of "internal documents", but there were still things you could not do. One of these things was the infamous "needle to the eye" motif, and when Todd McFarland drew such a panel, and refused to change it for his editors and publishers, this proved to be the straw that broke the camel's back, and we got Image Comics. Marvel left the Code a few years later, but DC continued to use it for some of its books because DC has always had a keener appreciation of the value of children readers. It's not a coincidence that the company which was creating Batman: The Animated Series was also still participating in the Code. DC also published Vertigo, and plenty of other books which did not use the Code, but they also wanted to have a large selection of books which, for example, Grandma could safely buy as a birthday present for her little boy. I honestly think Marvel left the code just because Joe Quesada was tired of dealing with the hassle of getting approval for every book. The content of the books didn't much change.

All of which leads us to the present, and DC's final decision to move away from the Code altogether and instead embrace a rating system similar to the one they already use on video games. I cannot help but think, with the benefit of hindsight, that this is what DC and other comics publishers should have pushed for from the beginning. But they could not, because they had already bought into the essential premise of their critics: that comics were for kids. That was an unfair assumption. But it was foolish to accept it. And the comics form paid the price. It has not yet recovered.

(1) -- The second book worth reading on this topic is Hajdu's The Ten Cent Plague: The Great Comic Book Scare and How It Changed America. Hajdu writes not as a journalist but as a storyteller and historian, which means his book has more of a narrative and is, in many ways, simply more fun to read. But it focused almost exclusively on the formation of the Code, and does not treat the Code's transformation in later decades. This makes it less useful to the comics scholar, but still a great book.

Wednesday, February 16, 2011

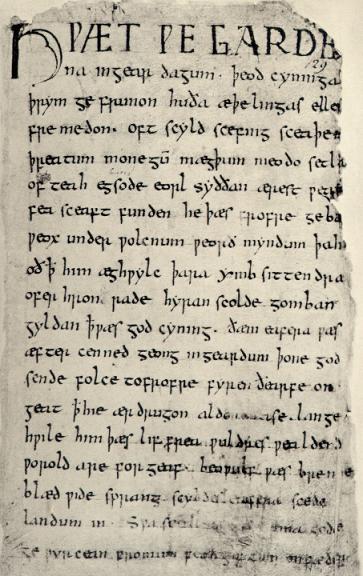

"A Book On Fire": A Brief History of Beowulf

This essay was written in 2007 for IDW's comic adaptation of Neil Gaiman's Beowulf film. It, and a second essay I wrote on Beowulf in comics, was printed in issue 3 and 4 of the original six-issue series, but the essays were not collected when the trade came out later the same year. I'm using Beowulf in one of my classes this semester, so I reprint the article here in the hope it may be useful to students.

-----

-----

A Book On Fire

The date is October 23, 1731, and words are burning. The Cotton Library, the world’s greatest collection of literature from the Middle Ages, has caught fire. Doctor Bentley, the library’s curator, staggers from the door clutching what might be the oldest, most complete copy of the Bible, dating from the 400s. That’s the book he’s chosen to save from the flames, but what has he left inside? Illuminated gospels, their magnificent pages covered in a thin layer of worked gold; a copy of the Magna Carta, some stories of the saints, histories of England, travel memoirs, poems, riddles composed by a long-dead wit … and the only copy of Beowulf.

Sir Cotton started his library when Henry VIII, he of the funny song and the many wives, impounded all the monasteries in England. Monks have a lot of books, but Henry was more interested in their money. The books went to Cotton, who suddenly became the owner of the greatest library in the English language. So he put all those books on shelves in a single big room and, to keep it all straight, he set busts of Roman emperors on each bookcase and labeled the books according to whichever marble head was looking down over them. Why use a boring decimal system or an online search engine when you can sort books by Julius Caesar, Caligula, and Vespasian? (While not an emperor, Cleopatra also had a bookcase in the library, and probably took some bitter pride in being the only woman in the room.) So there’s Augustus protecting the Magna Carta, Claudius with his copy of Genesis, Nero entrusted with the Lindisfarne Gospels and the only copy of the divinely haunting poem Pearl (perhaps Cotton felt Nero, more than anyone else, needed to get religion), and over in the case belonging to Vitellius – a heavy-drinking bum who shared his term as Emperor with a few others in the “Year of the Four Caesars” – on the top shelf, fifteenth book from the left, is the Codex we’re concerned with. The one that’s burning. I hope there’s nothing important in there.

To find out how Beowulf got into this kind of trouble, we have to go farther back. So keep your head down and don’t breathe the smoke. It is in the sixth century that the events of Beowulf take place; we only know this because he mentions a battle for which we have corroborating evidence. But although most of the action happens in Hamlet’s stomping ground of Denmark, the poem of Beowulf – and it really is a single poem, three thousand lines long – was told in northern England, two hundred years later, by Anglo-Saxons. These men didn’t consider themselves British; they were Viking through and through and their heroes were from the “old country”: Scandinavia.

We don’t know the name of the guy who eventually wrote Beowulf down onto thin sheets of shaved leather, but once he did that version of the poem was copied and recopied by ink-stained hands from one book to the next for another couple of hundred years until, by sometime in the 900s, it was put together with a story of Saint Christopher, a collection of outlandish anecdotes about a Far East that no one had actually been to, a (supposed) letter from Alexander the Great, and a poem about Judith. (She’s the Jewish gal who cut off the head of her oppressor, Holofernes. I bet Cleopatra wished Judith was on her shelf.) All these pages were sewn together into a single book and, about six hundred years later, combined with yet another book before being slid onto the top shelf under Vitellius, where it is now burning – the edge of each page going black, erasing Beowulf and all his deeds from human memory forever.

About a quarter of the Cotton Library was burned up before the fire was put out. If you were an evil genius with a time machine and you wanted to destroy Western civilization, you might start by setting your flux capacitor for 1731, warming up Mr. Fusion, and lighting that fire. Or, if you are more criminally inclined, maybe you’ll go back and steal an ancient tome containing Secrets Man Was Not Meant To Know, setting the fire to cover your tracks. (Come to think of it, I don’t know you. Where were you in 1731?)

Even though Beowulf survived, his pages blackened but not burnt up, he did not fare well in the years that followed. Those who learned how to read the poem’s Old English were confused by what they found. Here was a tale both pagan and Christian, with children of Cain in it but no Christ. Its champions invoke God, but don’t seem very charitable, merciful, or least of all humble. Their virtues are heroic ones of courage, duty, and hospitality, loyalty to family and lord. Structurally, the whole thing doesn’t make much sense – it has three antagonists instead of one, with the last separated from the first two by a fifty-year gap. So is Beowulf two parts, or three? Filmmakers have been frustrated by that fifty-year gap all the way to the present day. Most simply ignore it.

Beowulf doesn’t rhyme; it alliterates instead. And no iambic pentameter is to be found because according to the Anglo-Saxon storytellers it didn’t matter how many syllables a line had as long as it was short and had three alliterations in it. To old white guys used to Homer’s Odyssey and Virgil’s Aeneid, Beowulf just looked like bad poetry. And, worst sin of all, it wasn’t about high moral themes or the foundation of an empire, it was about a guy fighting monsters! Anything with trolls and dragons in it couldn’t possibly be taken seriously. The only people who could read Beowulf were scholars, and while they were too high-brow to say out loud that they considered it an inferior piece of crap, it certainly was no Iliad.

Enter JRR Tolkien. Yes, that Tolkien. The man who would go on to give us Aragorn, Frodo, and Sir Ian McKellan action figures happened to be one of those Ivory Tower Beowulf scholars and he didn’t just like the poem, he loved it. And like many of us who really love literature that critics despise, he came to its defense. In his 1936 essay Beowulf: The Monster and the Critics Tolkien wrote that the problem everyone was having with Beowulf wasn’t because the poem was bad, it was because everyone was trying to compare it to something it wasn’t – namely, Homer and Virgil. Beowulf didn’t conform to the rules of epic poetry because those rules were made up by ancient Greeks and Romans, not Scandinavians. The poem had a very solid meter, it just wasn’t one you counted in the traditional way. And that fifty year-gap between the fight with Grendel’s mother and the dragon? That gap was what made the poem so great. Beowulf is neither the story of a young hero who triumphs over monsters, nor the story of an old king who dies in a wasted effort to kill a dragon, but the combined tale of a man who, once young and impervious, advances with open eyes to his own inevitable and tragic death. You need both halves to make that story work. Tolkien’s reading of the poem woke everyone up to Beowulf’s hidden poetic mojo. Perhaps we should credit Tolkien with saving our book from that blazing library. It is no exaggeration to say that, without him, Beowulf would not now be read in high schools across America, would not be read by anyone except PhDs in medieval English, would not have films, novels, and comic books bearing his name.

Professor Tolkien didn’t just write about Beowulf; like a lot of good writers, he stole from it when he came to write his own fantasy masterpieces. After all, this was a guy who knew trolls and dragons were good stuff. In The Two Towers chapter “The King of the Golden Hall,” Aragorn and his companions arrive at the mead-hall of Meduseld, are stopped by a door-guard, forced to leave their weapons behind, and enter the hall only to be confronted by a white-bearded, helpless king and his weasely counselor. The entire episode is lifted straight out of the beginning of Beowulf, proving that even Oxford professors can swipe art. The name of King Theoden’s nephew Eomer appears in Beowulf, and Aragorn’s famous “Where is the horse and the rider?” poem, recited upon his arrival in Rohan, is actually another 10th century Anglo-Saxon song called “The Wanderer.” (These lines are given to King Theoden in Jackson’s film version.) The fire-breathing dragon of Beowulf, who sleeps on a mound of treasure underground but rises in wrath and anger after a thief makes off with a single object from his hoard, became the climax to The Hobbit (and countless fantasy imitators).

By the 1960s Tolkien was an American phenomenon and Beowulf had been translated into modern English more than once. So it comes as no surprise that John Gardner chose this material as the raw ingredients for his 1971 novel Grendel. Narrated in stream-of-consciousness style by the monster himself, Gardner’s is a book of existential philosophy with a little Marxist revolution and William Blake thrown in for spice. Grendel is fully intelligent and convinced that the world has no meaning, that life is just a continuous series of accidents without purpose or hope. He shouts at the sky, knowing the sky will not answer. He hunts Hrothgar’s men not because he hates them (and he does) but because he is hungry and bored. He consoles himself that by preying on these 6th century warriors, he is making them into heroes. He’s giving their universe meaning. When music, storytelling, and love threaten to impose a man-made meaning on his life, Grendel feels both fear and wrath. Eventually Beowulf shows up and rips our narrator’s arm off; the last thing we see is Grendel standing at the edge of Nietzsche’s abyss, staring into it. Gardner’s descriptions of the daily life of the Northmen (Grendel spies on them obsessively from cover of trees and cowsheds) are the best parts of the book. As odd as Grendel sounds, it was very influential and the first depiction of Beowulf on film is actually an adaptation of Gardner, not the poem. Grendel Grendel Grendel was an Australian-made animated feature in 1981 with the great Peter Ustinov supplying the voice of the monster/narrator.

Beowulf had gotten a larger audience, but to many it was still too boring for words – the perfect example of a literary work that no one would read by choice. Michael Crichton (he of Jurassic Park fame) felt differently and after a hot little argument with Professor Kurt Villadsen in 1974 he decided to show the world how interesting Beowulf could be. He did this by removing all the trolls and dragons, turning myth into the historical fantasy Eaters of the Dead. In this version of the story, Beowulf is a 10th century Viking accompanied on his quest by Ibn Fadlan, an Arabic traveler who really existed and whose travel diaries Crichton had read in high school. Instead of John Gardner’s emo Grendel we have the “wendol”, the last tribe of Neanderthals. They worship cave bears and eat anyone slow enough to get captured, maintaining their terrifying reputation by never leaving their own fallen behind and only attacking when they have cover from a black mist that blows down from the hills. In the poem, Beowulf (who Crichton names “Buliwyf,” and maybe that is my issue with the novel, because I cannot read “Buliwyf” without thinking of D&D’s Bullywugs, and now in my mind’s eye Beowulf is transformed Thor-style into a goggle-eyed toad) has to descend into a lake infested with sea monsters to kill Grendel’s monstrous mother, but here he rappels down a cliff to the sea-bound cave of an ancient woman with snakes in her hair. A dragon? Oh no: torch-bearing dudes on horses. This, children, is how everything fantastic, mystical, and awe-inspiring in the world is reduced by numbers to listless mundanity. Crichton wrote an interesting adventure story, but it’s no Beowulf.

It makes for good Hollywood though! Those of you paying attention can see by now that people don’t make movies based on Beowulf, they make movies based on books other people have written about Beowulf. John McTiernan’s version is The Thirteenth Warrior, a pretty solid adaptation of Crichton’s novel and probably Antonio Banderas’s Second Best Flick (for those keeping score: Mask of Zorro). Banderas’s ibn Fadlan is much more heroic than he is in the novel, kicking wendol ass with his scimitar of fury, though the dudes on horseback still don’t make a very convincing dragon. The haunted, distant, but Herculean hero called Beowulf is well presented in this film, and that’s why it rises above its source material. Crichton’s Scandinavian hero is foreign and remote; anyone trying to understand him may as well be reading Old English poetry. It’s more creative. But McTiernan gives us a man we can sympathize with, feel for, and admire, despite (maybe even because of) the way he distances himself from everyone close to him. He may not be mythical, but he’s real.

Thirteenth Warrior didn’t do especially well at the box office, but it was the opening shot in a firefight of Beowulf films which reminds me of nothing so much as the storm of Robin Hood movies which unjustly smothered Dave Stevens’ Rocketeer (but I’m not bitter). In the same year that it was released, 1999, we got a different version of Beowulf starring Christopher Lambert. Like Banderas, Lambert has done a very few good flicks (for those keeping score: Highlander) and a whole lot of really bad ones, and Beowulf is one the latter. A Road Warrior-style apocalyptic wasteland replaces 6th century Scandinavia in this version, probably because post-apocalyptic wastelands are notoriously cheap to film. Writer Mark Leahy plays fast and loose with the cast of the poem, keeping the character of Beowulf’s rival Unferth but changing his name to Roland because, well, one heroic poem is as good as another, right? (The Song of Roland is, of course, the national epic of France, and is a wonderfully good tragic poem in its own right about a different guy who goes up against overwhelming odds, triumphs for a while, and then dies. No relation.) The obligatory ginsu girl sex object is Hrothgar’s daughter Kyra. Everyone’s got a secret in this movie, though none of them are very interesting: Roland may have killed Kyra’s husband, Grendel’s mother seduced Hrothgar way back when and that’s where little monsters come from, and Beowulf himself is the son of Baal, “God of Darkness and Deceit.” (This explains his ability to regenerate from injury, but not his bad fight choreography.) Grendel’s mother transforms from a bottle-blonde vixen to a multi-armed fleshless spider-woman but, trust me, it reads a lot cooler than it looks.

Before Gaiman came to Beowulf, the last big-screen adaptation was Sturla Gunnarsson’s 2005 Beowulf and Grendel, starring Gerard Butler. Now, for hardcore fans of the monster-slaying Geat, this film is not bad. It’s got a realistic depiction of Viking life (complete with Sutton Hoo helmets for Beowulf and his buds) and is shot on location. Gunnarsson ditches the entire dragon encounter and, like Crichton and Gardner, humanizes Grendel into a sympathetic outcast, not a troll but an Andre-the-Giant-sized man who’s grown up in a cave with no company besides his old man’s skull – delivered unto him by Hrothgar at the film’s beginning. So Grendel’s murders are all justified, you see, and it isn’t until Beowulf and his men defile said skull that the kid gets really mad, leading to the armless slugfest, the attack of Grendel’s misshapen mom, and a climax which brings physical victory but moral and ethical compromise. Once he cut off the entire second half of the poem, Gunnarsson didn’t have a whole lot of story left, so he embroidered a beauteous red-haired witch (you thought the Marvel Universe had the trademark on those, didn’t you) who serves as love interest to both hero and monster. There’s really only two problems with Beowulf and Grendel. The first is the idea that a woman who has been raped would then befriend and protect her rapist; that just makes the back of my throat taste bad. The second problem is this: Batman: Year One is a great read, but it is ten times better if you can also read Dark Knight Returns. If Gunnarsson hadn’t amputated the poem’s payoff by ignoring the dragon episode, he wouldn’t be scraping so desperately to give Beowulf some meaning.

Earlier I said that Beowulf survived the inferno in the Cotton Library way back in 1731, that the fire was eventually put out. But I wonder if I wasn’t too hasty. Tolkien’s passion for the poem brought it to our attention in the first place, Gardner made a speechless monster into a long-winded philosopher, and Crichton and McTiernan tried to make it all real. This year there are not one but two film versions of Beowulf to come out in theaters (the other: Beowulf: King of the Geats). And it is exciting to see what Gaiman, one of comics most brilliant and creative writers, is doing with this deceptively-primitive tale. It seems to me now, looking back, that the fire is still raging inside Vitellius’ bookshelf. Flames are licking at the pages of Beowulf and we’re only now reaching out with our pink unprotected fingers, willing to be burned as long as we get a peek inside.

Posting on Comic Book Therapy

With a hat tip to James Elmore who turned me on to the site, I have begun blogging for the comics news site known as Comic Book Therapy. I tried to start small, with a simple review, but sometimes things that seem small lead to places most revealing, and so it was with this.

I started off talking about The Cape's latest episode, called "The Lich."

Wednesday, February 9, 2011

Podcasting

When I am fortunate, I am invited to appear on Mike Lafferty's Vigilance Press podcasts. We've done two in the last week. The first focuses on the USHER Dossiers and is much enlivened by the fact that Mike had a few glasses of wine. He must be a cheap drunk. Mike also prompted me for a review of the recent Green Hornet film and Jon and I got into British comics when no one else was looking.